People magazine: Three-Star Review, February 21, 2011

The Washington Post, March 27, 2011

Los Angeles Times: Discoveries, February 13, 2011

The Oregonian: Spring’s Fresh Harvest of Food Memoirs, April 5, 2011

The Daily Beast: This Week’s Hot Reads, February 26, 2011

San Francisco Chronicle, March 6, 2011

Winnipeg Free Press: Endearing Tale of Food, Culture, Ethnic Ties, February 12, 2011

The (Fort Worth) Star-Telegram, June 21, 2011

Library Journal Reviews, January 1, 2011

The Key West Citizen, May 26, 2013

Lonely Planet, December 14, 2011

The Charlotte Observer’s South Park magazine, July 8, 2011

Expat Living Magazine, June 20, 2011

Hyphen Magazine, June 15, 2011

San Angelo Standard-Times, February 15, 2011

Brooklyn Bugle, September 9, 2011

Tasting Table, September 1, 2011

BookReporter.com, February 12, 2011

Radio

National Public Radio’s Morning Edition: Singaporean Cuisine of All Stripes, Courtesy “A Tiger”

Midday With Dan Rodricks on WYPR in Baltimore

Wisconsin Public Radio: Celebrating Chinese new year with A Tiger in the Kitchen

WGN Radio: The Sunday Papers with Rick Kogan

Delicious Mischief with John Demers on KTRH News Talk Radio AM740 in Houston

National Public Radio: Know your ‘Tiger’ Books; A Primer with Stripes On

Azumano Travel Show on KPAM in Portland, Ore.: Tigers Versus Ghosts in Singapore

Southbound Food on Houston’s KGOW, AM 1560 The Game

TV

Fox 26 News in Houston’s Morning Show: Author Cheryl Tan’s Gambling Rice

International Channel Shanghai (ICS): A Tiger in the Kitchen in Shanghai

WXYZ-TV (ABC) Detroit’s Weekend Morning Show: Making Mooncakes with A Tiger in the Kitchen

WZZM-TV (ABC) in Grand Rapids, Michigan: A Tiger in the Kitchen Author Shares Mooncake Recipe

Channel News Asia: Primetime Morning

Razor TV (SIngapore): Singapore Author’s Kitchen Confidential: A Tiger in the Kitchen, Part 1

Razor TV (SIngapore): Illegal Gambling Den and Opium Addict: A Tiger in the Kitchen, Part 2

Razor TV (SIngapore): From Fashion to Food: A Tiger in the Kitchen, Part 3

Razor TV (SIngapore): Her Mother’s Kong Bak Pau: A Tiger in the Kitchen, Part 4

Sinovision: A Tiger in the Kitchen

Print (back to top)

The Washington Post: Family Recipes: Our Ties to the Past, If We Preserve Them

The Denver Post: Family Memoir Fills Ache for Singaporean Cooking

Shanghai Daily: Food Comes From The Heart

New York Post: Such Great Heights, Cheryl Tan Lives and Writes in Brooklyn

The Wichita Eagle: Memoir Shares Joys of Cooking, Culture, Family

The Sacramento Bee: Singapore’s Cuisine Revealed in “A Tiger in the Kitchen”

Detroit Free Press: Cookbook Details Author’s Second Chance to Cook Like Her Singapore Grandma

New York Daily News: Food Bloggers Share Chinese New Year Recipes

Publisher’s Weekly: A Singaporean Chinese New Year lunch with A Tiger in the Kitchen

Medill magazine of Northwestern University: A Taste of Home (Page 11)

The Record: Here’s To Memories and Dishes Just Like Moms Used to Make

The Houston Chronicle: New Book Titles Share a Theme: Tigers

San Jose Mercury News: Top Five: Tigers Popping Up Everywhere

Lianhe Zaobao (Singapore): Hometown Food Embodies Childhood Memories

The Times (South Africa): A Family Affair

Voices: Author Rediscovers Identity Through Food Memoir

Web Sites (back to top)

The Washington Post: Live Q&A with Author Cheryl Tan on Food, Family and Recovering from a Layoff

Oprah: What Book to Read Next: “A Tiger in the Kitchen”

The Wall Street Journal: The Best in Asia and Asian America

The Atlantic: In Singapore, Ghosts Are Real, Scary And Hungry

The Baltimore Sun: A Tiger in the Kitchen: A Mouth-Watering Read

Cosmopolitan: Easy Ways to be a Goddess in the Kitchen

Oprah: Your Mom’s Meatloaf Recipe Might Be More Important Than You Thought

PBS: Discover The Hungry Ghost Festival of Singapore

Forbes: This Time the Tiger’s in the Kitchen: Q&A with Cheryl Tan

Kirkus: Rediscovering Singapore, One Recipe at a Time

Biographile: A Tiger in the Kitchen, Q&A with Cheryl Tan

The Beijinger: Another Tiger Woman, This Time In The Kitchen

Inc. Magazine: Building A Personal Brand

Atlanta Journal Constitution: Author of Singaporean Food Memoir to Speak at Decatur Book Festival

Asia Society: Culinary Diplomacy Served at Singapore Embassy

Her World Singapore: Cooking From The Heart

Cowgirl Chef: Cheryl Tan at the Paris Cookbook Fair

Houston Chronicle: What’s With All The Tigers?

InsatiableCritic.com: Tiger In The Kitchen

Curled Up With A Good Book: “A rich culinary adventure filled with history and culture”

Book Journey: “Mouth-Watering Sensation of a Book”

Book Journey: Author Chat with Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

Poynter: “January was all about the Tiger Mom. February has A Tiger in the Kitchen.”

Writerland: Author Interview: Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

Fresh Fiction: Jen’s Jewels Interview with Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

FlavorWire: Cheryl Tan’s “Delicious Tales to Read in the Kitchen”

NBC’s The Feast: Inspiration for “A Tiger in the Kitchen”

Culinate: Away From Home: Memoirs Explore the Meaning of Family

Book Q&As with Deborah Kalb: A Tiger in the Kitchen

Vital Juice: Vital Spy: Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan; This Fashionable Foodie Dishes on Her Favorite Finds

BlogHer: Making Chinese Mooncakes with “A Tiger in the Kitchen”

The Daily Meal: Why Singapore is Food Obsessed and More

MidtownLunch: Profile of Midtown Luncher Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

Marjolein Book Blog: Fabulous Books for the Year of the Dragon

Brooklyn Bugle: Restaurants and Recipes from Cheryl Tan, Author of “A Tiger in the Kitchen”

Brooklyn Heights Blog: A Tiger in the Kitchen in Brooklyn Heights

Neal Thompson: A Day at The Office: Authors Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan & Peter Mountford

The Gastro Gnome: 5 Reasons To Read “A Tiger in the Kitchen” Today

Epicurious Travelers: Books We Love: A Tiger in the Kitchen

SCC Library Reads: A Tiger in the Kitchen

The Asian Cajuns: “It’s Eat, Pray, Love meets Julie and Julia … with Asian food”

Northwestern University Alum Talks: Cheryl Tan

Asian Talent Online praises the “masterful prose” in “A Tiger in the Kitchen”

The Naptime Chef: Eight Great Spring Book Recommendations

Kristin Pot Pie: Becoming A Woman: “A Tiger in the Kitchen” by Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

Eye See Style: Author Cheryl Tan Roars Into Decatur Book Fest

Food Monsters: Cheryl Tan and Gigi’s Asian Bistro

Lisa is Cooking: “Cheryl Tan: What are you Reading?”

Notabilia calls A Tiger in the Kitchen “humorous, informative, and well-written.”

If The Shoe Fits: Read It: A Tiger in The Kitchen

Overseas Singaporean Unit: Q&A with Author Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

The New Perfect: On Food, Family and Memory-Making

The Literary Rapport: Review of A Tiger in the Kitchen

Our Chinatown: A Tiger in the Kitchen

Euro RSCG Worldwide’s Fashion Blog: Cheryl Tan on Food and Fashion

Mousey The Librarian: “I love it!”

Cheryl By Cheryl: Three New Books by Cheryls

Peter A. McKay: Who Says You Can’t Sign an E-Book?

Kirkus, December 15, 2010 (back to top)

Publisher:Voice/Hyperion

Pages: 304

Publication Date: February 8, 2011

ISBN ( Paperback ): 978-1-4013-4128-2

Category: Nonfiction

Classification: Biography

One woman’s quest to reconnect with her family by way of traditional Singaporean food.

Tan’s debut memoir explores the connection between taste buds and memory. After her parents’ unexpected divorce—as well as falling victim to a brutal restructuring at Wall Street Journal—the author took advantage of her newfound freedom to return home to Singapore, dedicating a year to culinary adventure. She hoped to reacquaint herself with both her family’s recipes and her family itself. Written in the tradition of two classic but different memoirs, Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior (1976) and Julie Powell’s Julie & Julia (2005), the book is a recipe in itself—a dash of conjuring the ancient stories of one’s past, a sprinkling of culinary narrative. The result is a literary treat filled with Singaporean tradition, including the surprisingly significant role food plays in the Festival of the Hungry Ghosts and the Moon Festival, among others. Tan argues that stories themselves are a kind of sustenance, and that the oral tradition, like food, begins in the mouth and ends in the stomach. She notes that her journey to Singapore was an attempt to “retrace [her] grandmother’s footsteps in the kitchen,” yet she retraces the steps of other relatives as well, including aunts and her mother—all of whom yield information far beyond the recipes. “Cooking wasn’t a science; it wasn’t meant to be perfect,” she writes. “It was simply a way to feed the people you loved.” As readers meet these loved ones, the narrative becomes all the more engaging. For Tan, cooking functions as a moderator between family members, allowing her to serve all their stories in the proper portions.

A delightful take on the relationship between food, family and tradition.

People: Three Stars, February 21, 2011 (back to top)

After losing her job as a Manhattan fashion writer, Tan visited Singapore to master her family’s recipes. Her prose is breezy, and her descriptions of duck soup and pineapple tarts entice. But the meat in this memoir is what Tan learns about her resilient family, whose members come together both to cook and to heal.

Reviewed by Beth Perry

Los Angeles Times, February 13, 2011 (back to top)

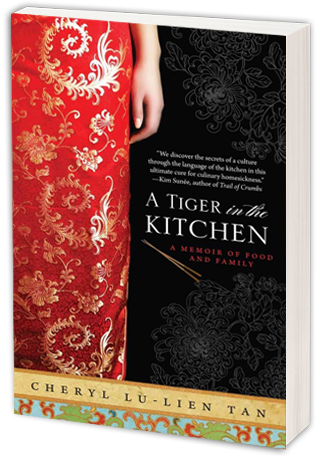

A Tiger in the Kitchen; A Memoir of Food and Family

Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

Voice: 292 pp., $14.99 paper

This memoir is less controversial, more inspirational than Amy Chua’s fiery book on Chinese parenting. Singapore-raised and American college-educated, Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan rushed down the career path, her father’s voice in her head, before pulling up short with a longing for her past. Living on bagels, ramen and hamburgers, Tan realized she had become a food exile.

Memories of the Teochew (a Chinese ethnic group in Singapore) recipes her aunties and grandmother made (lotus-seed-filled mooncakes, duck every which way, spring roll-like popiah rolls, bird’s nest soup) crowded her days in New York City, where she had lived for 17 years. Tan spent a year collecting the fusion recipes — the blend of Chinese, Indian and Malaysian — that make up the comfort food of Singapore. Tan’s tiger qualities reveal themselves in her fierce determination to draw her past into her present, to slow down, to learn how to make the food of her childhood.

The Oregonian, April 5, 2011 (back to top)

A Tiger in the Kitchen: A Memoir of Food and Family

Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

Voice/Hyperion, $14.99 (paperback); 304 pages

The Chinese zodiac says 2011 is the Year of the Rabbit. Book

publishers, though, seem to think it’s the Year of the Tiger. So far,

tigers have appeared in the titles of two memoirs (Amy Chua’sBattle Hymn of the Tiger Mother and Margaux Fragoso’s Tiger, Tiger) and an acclaimed first novel (Téa Obreht’s The Tiger’s Wife).

Now Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan’s A Tiger in the Kitchen: A Memoir of Food and Family pads into the fray. A former fashion reporter, Tan was laid off from The Wall Street Journal during the paper’s 2009 budget cuts. Almost instantly she decided to spend a year in her native Singapore learning to make traditional dishes she remembered from childhood.

In the ensuing 12 months, Tan’s aunties wind up teaching her something far more important than how to make pineapple tarts (though she learns that skill, too). By example, they demonstrate the roles of patience and informed observation in the kitchen. Eventually Tan learns to tamp down her innate perfectionism and earns her stripes as a real cook.

Intergenerational dynamics, cultural misunderstandings and culinary blunders all contribute to the story, but the book’s focus rarely shifts from the food itself. Tan’s simple, loving descriptions of traditional dishes make the mouth water — luckily, 10 of her family’s recipes are included at the book’s end.

The Daily Beast: This Week’s Hot Reads, February 26, 2011 (back to top)

A Tiger in the Kitchen: A Memoir of Food and Family

Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

A Chinese-Singaporean expat leaves behind fashion journalism in New York to revisit her culinary roots overseas.

Born in the Year of the Tiger, rebellious Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan left her home in Singapore to pursue journalism in America when she was just 18—but some 15 years later, she found herself yearning for her native country’s culinary traditions and the ambrosial meals that shaped her early life. Chronicling her quest for self-discovery through food, Tan’s A Tiger in the Kitchen is reminiscent of Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love, yet the author’s determination to master her grandmothers’ and aunts’ recipes also echoes the triumphs and struggles in Julie Powell’sJulie & Julia (Tan also maintains a blog, www.atigerinthekitchen.com.) Above all, A Tiger in the Kitchen is a tale of reconnecting with family and tradition—with the fried rice and flaky pineapple tarts that define Singaporean culture—and of food’s sensorial power to connect us to our pasts.

The Washington Post: March 27, 2011 (back to top)

A Tiger in the Kitchen, a memoir by Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

Early in this savory memoir, New York writer Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan gives a sense of the caution that pervades Singapore, the city of her birth. When she called to tell her parents about her new boyfriend and mentioned his surname, Nakamura, her father pointed out that her two aunts had been killed by the Japanese. “I would have to tell him several times,” she writes, “that the boyfriend was a third-generation American and could not possibly have been responsible for the Japanese occupation of Singapore during World War II.”

It also took some persuading before Tan’s parents came to terms with her decisions to attend college in the United States and then to settle here. On a visit home, she realized that her grandmother, at least, had reconciled herself to the uprooting when Ah-ma agreed to teach her how to make popiah, a roll “filled with a melange of ingredients like minced shrimp and jicama.” “She had never wanted me to be away from her,” Tan writes. “But now that I was, and now that I might have a family of my own there someday soon, she wanted me to listen up and learn.” At the end of the book, having deepened her relationships with several other relatives, Tan gets her mother to tell her how to make one of Asia’s most labor-intensive delicacies: bird’s-nest soup.

San Francisco Chronicle, March 6, 2011 (back to top)

‘A Tiger in the Kitchen,’ by Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

By Terry Hong

Sunday, March 6, 2011

A toothsome distraction from the recent Tiger Mother hunt, journalist Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan offers “A Tiger in the Kitchen: A Memoir of Food and Family,” which takes readers from Carnegie Hall into fragrant kitchens, trading threatened stuffed animals for pineapple tarts, Prokofiev for pandan.

Tan’s strong-willed tiger streak had kept her “deftly” out of the kitchen, growing up privileged in Singapore, but fueled her academic excellence, her solo immigration to the United States at 18, and her eventual glamorous New York City career as a fashion writer.

Despite comical culinary inexperience marked by “rather unfortunate episodes,” Tan was convinced that with “a Singaporean grandmother who was both a force of nature and a legendary cook … I believed it was in my blood to excel in the kitchen – or at least kill myself trying.”

A serendipitously timed layoff from her Wall Street Journal job – mixed with concern over her parents’ family-splintering later-in-life divorce – sends Tan to Singapore on and off for a year, where her relatives generously welcome her, not only to satisfy her culinary quest but also to feed her heart and soul with lost and forgotten family stories. As Tan masters her favorite childhood dishes, she also realizes “that the point hadn’t truly ever been the food.”

Between braised ducks and moon cakes, Tan learns of gambling ancestors, opium addiction, abusive first wives and foundling uncles.

Her “Tiger” is fiercest when recording such familial histories, albeit occasionally weakened with quips about ruined manicures and designer shoes. Her debut fare proves a light appetizer, but with promise of a substantial meal yet to come.

Winnipeg Free Press, February 12, 2011 (back to top)

Endearing tale of food, culture, ethnic ties

A Tiger in the Kitchen; A Memoir of Food and Family

By Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

Voice/Hyperion Press, 304 pages, $15

New York-based journalist Cheryl Tan used to be hopeless in the kitchen, but not anymore. In fact, she has written an engaging memoir about a year-long cooking adventure in her native Singapore.

Not only did she master many of her favourite recipes, the way famed blogger Julie Powell did with the French cooking of Julia Child, but she bonded with relatives from her large extended family.

Tan has lived and worked in the U.S. for the past 16 years but she gives no indication of having been inspired by Powell’s story. In 2008, she already knew how to cook North American style, yet she yearned for the ethnic Singaporean dishes of her childhood.

During a period of unemployment, she had the opportunity to travel to Singapore. So she sought out family members to give lessons in her late grandmother’s traditional cookery.

Tan’s writing style is frank and lively. She divides her book into 18 short chapters followed by a sampling of traditional Singaporean recipes. The book’s aptly chosen title refers to the Year of the Tiger, in which Tan was born as well as her stubborn and aggressive nature.

After witnessing one of Tan’s childhood temper tantrums, her aunt called her a “Tiger baby.”

Interspersed within the narrative are details about the culture of Singapore, a tiny Southeast Asian country whose cuisine reflects a myriad of influences: British, Chinese, Malay, East Indian and European. Readers will learn about several Singaporean food-related customs, such as at weddings and other celebrations like the Festival of the Hungry Ghosts and the Moon Festival. On an interesting note, one dish called “gambling rice” was invented for card players who didn’t want to leave their game; thus, the food is eaten with one hand.

Often Tan’s adventures are presented as vignettes. Her first cooking experience in Singapore involved numerous steps in making pineapple tarts for the Chinese New Year. Never did Tan imagine that her aunt would assemble 70 pineapples to produce 3,000 tarts! On the other hand the curious dish, bird’s nest soup, is easier to make than she expected.

One outcome of Tan’s culinary journey is her newfound knowledge of family lore. From her aunt, a straitlaced vice-principal, she discovers some tantalizing secrets. (“Oh, did I tell you I was an opium courier for your great-grandfather? Or that he was a gambling addict?”)

Throughout the book, Tan’s self-deprecating humour adds an element of levity to the book. At the outset, she pokes fun at her North American cooking failures. “An Oreo cheesecake pie I attempted for Thanksgiving turned out so lumpy that one guest gently inquired if I owned a whisk. (Hello, if I needed one, perhaps the recipe printed on the back of the piecrust label should have said so?)

With Singaporean food, her culinary misfirings happen only occasionally. For her grandmother’s chicken curry recipe, “the much more concentrated canned milk made the gravy incredibly thick; instead of it being like a thick soup, it was a little like ectoplasm.”

This book about food, culture and ethnic ties is written with an openness that will endear Tan to her audience. Readers who enjoyed the memoir Tender at the Bone: Growing Up at the Table by food critic Ruth Reichl will also enjoy A Tiger in the Kitchen.

Library Journal Reviews, January 1, 2011 (back to top)

A Tiger in the Kitchen: A Memoir of Food and Family

By Courtney Greene

Tan embraced the rebelliousness associated with the Year of the Tiger, leaving her native Singapore first to study and then to work in the United States—not as a lawyer as her father had hoped but as a journalist. A desire to reconnect with her family and culture led her on a yearlong project to learn to cook the food of her childhood, commuting between her homeland and her chosen home, taking “lessons” in Singaporean cooking from her aunts. In this humorous and heartfelt memoir, she charts her progress with a deft hand, whether focusing on cooking, negotiating family dynamics, or what she thinks of herself. Tan, who also maintains a blog of the same name (www.atigerinthekitchen.com), includes ten recipes. VERDICT Those wishing to school themselves in the dishes of Singapore are better off with a cookbook, but this warm, witty chronicle of growing up and finding one’s place between cultures will be widely enjoyed. Recommended.

The Key West Citizen, May 26, 2013 (back to top)

A Tiger in the Kitchen by Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

Hyperion Press, $14.99

Reviewed by Jessica Argyle

After losing a prized newspaper job at the Wall Street Journal due to the great downturn of ’09, Cheryl Tan took a year off to return to her native Singapore and the comfort food of her youth. After meeting with her briefly, I am not surprised that she chose a difficult time to write a book, using her misfortune brilliantly. Reasons for her dexterity became evident once I got to know her family in A Tiger in the Kitchen.

Although Tan, a capable, goal-oriented type A, seamlessly negotiated the transition to America, could she do the same in reverse? Especially when she had largely rejected cooking for family, viewing a life in the kitchen as cut off from the larger world and lacking in power. Now, after 16 years in America, Tan must finally contend with the ladies and earn her place in the kitchen.

Slowly she learns to abandon the American obsession for precise measurements, formulas and procedures and begins to navigate complex recipes that often exist only in the sharp and exacting memory of one of her aunts. When she asks how much sugar to add or how long the duck should cook, she is often met with the words “agak, agak,” loosely translated as “just enough” or “until it is done.”

But over time spent with her aunties and mother, in the many hours it takes to properly prepare the cookery that fuses Malay, Indonesian and Chinese roots, Tan begins to see these women more clearly. She claims that although she has encountered tough and capable women in America, including driven CEOs and editors, nobody scared her more than these women in their Singaporan kitchens.

Over the course of chopping, peeling, dicing and boiling, stories begin to unfold, as appetizing as the dishes themselves. Memories are offered up that would never have surfaced otherwise. Divorce, opium addiction, love and abandonment, the stuff that families are made of are handed to Tan as a gift for genuinely participating in the family legacy.

Although I am not ordinarily fond of memoir cookery books, this one masterfully segues from kitchen to chronicle with natural cadence. I feel I know these characters, the aunts and the uncles, the father and mother and grandmother on their own terms. When I actually attempted her recipe for mandoo (a Chinese dumpling), I felt many eyes upon me, looking over my shoulder, silently letting me know that I could be quicker and the pleats in the dumplings neater and I could have used less filling to be tidy. And at the same time, I am convinced that they want me only to do my best — I really want to please them!

“Tiger” is both a frothy cocktail and a delicate family tale that shifts from continent to continent, past to present and culture to culture with an intuitive grasp of the precise moment to move on. Tan’s journalism background comes to the fore with clear, detailed writing, bringing us to a tempting table laden with exotic treats. It neither veers into an overly sentimental journey or a hard-nosed dissection of the shortcomings of either culture.

I met Cheryl Tan, an artist-in-residence at The Studios of Key West, on the deck and when I left her after our short meeting, she left me with star anise, a small bag of her own taco seasonings, Serrano chilies and a thick Singapore soy sauce. I have seen the leavings of other residents: the shameful empty wrappers, frozen dinners and remnants of gas-station chicken. Yes, she really does love to cook.

And by the way, the mandoo was delicious.

Epicurious, July 20, 2011 (back to top)

‘A Tiger in the Kitchen’

by Joanna Rothkopf

Although Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan’s memoir, A Tiger in the Kitchencame out this past February, it’s worth a summer read. In the book, the former Wall Street Journal fashion reporter recounts a year of commuting between New York and Singapore in the hopes of learning more about her culinary roots, and in the process demonstrates a growing knowledge and appreciation for her Teochew and Hokkien backgrounds. While fairly formulaic, the narrative manages to remain dynamic, getting its heft from ample description of her mouth-watering childhood dishes and anecdotes from Tan’s worldwide travels.

Readers enter on Tan entrenched in the glamorous New York fashion world, caught up in the unrelenting grind of the media industry. And we follow the author to Paris and Milan, to elegant party after exclusive fashion show, taken on a veritable tour of high-end Western culture of aesthetics.

This storyline would have perhaps weighed on readers for being too referential had it not been for her frequent visits to her home in Singapore, during which her “aunties” teach her the ins and outs of traditional dishes. Certainly, Tan has written some of the most appetizing passages in recent food writing, about mooncakes and braised duck and, of course, the exalted pineapple tarts that started it all. Interspersed throughout the rich stories of Tan in the kitchen surrounded by doting and clucking aunties are conversations with her family members, in which she unearths a family history that she had been previously too distracted, too unconcerned to discover.

Her Singaporean culinary exploits occur alongside her participation in an online Bread Baker’s Apprentice challenge during which she attempts, with varying levels of success, to make her way through Peter Reinhart’s baking bible. She describes the process of challah, bagels, and less successful ciabatta with humor, but also with the tenderness of one who recognizes past follies.

In the narrative, the precision and necessary accuracy of both bread baking and Wall Street life is put in unexpected contrast with the instinctual, estimating, feel-it-in-your-gut nature of Singaporean cooking. Oftentimes, when Tan attempts to record a certain measurement of flour or oil, she is chastised with the instructions to “Just taste, taste, taste, and then agak-agak lor!” The refrain means “guess-guess” and is a welcome respite, especially in more relaxed summer months, from the stress and pressure of a pervasive cultural perfectionism.

A Tiger in the Kitchen preaches a surrendering of that control in favor of experimentation, occasional vulnerability, and ultimate self-discovery. What’s more, is that Tan finally rewards hungry readers at the end of the memoir, with many of the recipes mentioned in the narrative–with accurate measurements for our American sensibilities.

Rating: 3 1/2 forks

The Straits Times, April 10, 2011 (back to top)

A TIGER IN THE KITCHEN by Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

*** 1/2

A Tiger In The Kitchen describes mee siam, chicken rice and other

staples of local cuisine with such gentle passion that the book is

best read in proximity to hawker centres or, at least, a well-stocked kitchen.

Aptly subtitled A Memoir Of Food And Family, this book from US-based Singaporean Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan is a tasty blend of gastronomic colour and family anecdotes, served with a dash of chick-lit style.

On a one-year mission to master childhood favourites and conquer an ostensible fear of cooking complex food, the journalist exchanges a Brooklyn apartment for kitchens in Hougang. She not only learns to fold rice dumplings and carve duck meat, but also rebuilds connections with relatives she left behind half a lifetime ago.

In between covering simmering pots, she uncovers family secrets, such as the fact that her late grandmother had to run a gambling den to put food on the table.

Reminiscent of fellow feature writer Sallie Tisdale’s book on American food culture, Best Thing I Ever Tasted, Tan’s A Tiger In The Kitchen will appeal to all who enjoy Singaporean cuisine or suffer twinges of nostalgia for dinner the way mum or grandma made it – sadly, men of that generation are absent from domestic kitchens in this text.

While entertaining and often touching, the story suffers from a slight identity crisis, as the author teeters between a feel-good family saga and chick-lit appeal. The occasional references to Bergdorf Goodman and $15 manicures seem too hard an attempt to reach out to fashionistas.

For the most part, reader interest is retained by descriptions of

family feasts and hawker treats that just skirt the edge of

gastronomic erotica.

Tan’s competent prose is elevated to poetry by her honest yearning for home-cooking and affection for the relatives who teach her. This is a nice snack from a first-time book writer and leaves the reader happy and hungry for more.

Expat Living Magazine, June 20, 2011 (back to top)

A Tiger in the Kitchen

Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

Voice | 296 pages

By Verne Maree

New York-based writer Cheryl Tan is a Singaporean who left her mother country at 18. Like many Singaporeans, she never learnt to cook; but in her thirties, she decided to do just that.

This autobiographical story sees her coming back to Singapore to learn family recipes from her grannies and great-aunts; it is at once a culinary odyssey and a journey towards reconciliation with her roots and her culture.

Competent cooks may find her initially abysmal ignorance unlikely – she really had no idea how to make fried rice? – or yawn at culinary near-disasters perhaps included mainly to create suspense. But if you want to know how to make pineapple tarts, mooncakes, otak or Teochew braised duck, get hold of this book. It ends with detailed recipes for these and more, painstakingly gleaned by Tan from her elderly relatives.

More than that, it offers interesting glimpses into Singapore’s culture and recent history.

The (Fort Worth) Star-Telegram, June 21, 2011

(back to top)

Delish reads: Authors’ family recipes redefine comfort food for the Cowgirl Chef

By Ellise Pierce

PARIS — I realize how crazy it sounds to take a 6:15 a.m. metro ride across town to go to yoga, but this is what I do every day.

How I pull off this early morning madness: (1) My boyfriend is my alarm clock — he wakes me up at precisely 5:30 a.m., and hands me (2) a very small, very strong coffee, which I throw back like a shot of tequila. I then shower, and get to the metro as quickly as possible and find a single seat by the window so I can spend the next 25 minutes with (3) a very good book.

Which lately has meant a couple of just-released fabulous food memoirs: A Tiger in the Kitchen (Hyperion, $14.99), by Cheryl Tan, and Day of Honey (Free Press, $26) by Annia Ciezadlo. I devoured both in a week’s time on the train, and by the time I’d put my toes on my yoga mat, my stomach would be awake and growling, wanting to taste everything I’d been reading about.

In A Tiger in the Kitchen, Tan took me along on her journey from Brooklyn to Singapore, where she learned how to make family recipes from her childhood, since the kitchen was the last place that you would find her when she was growing up. A first-born child who arrived in the Year of the Tiger, Tan’s determination and razor-sharp focus helped her sail through academia and took her to Illinois and then to New York, where she landed a job with The Wall Street Journal, reporting on fashion until she was laid off a couple of years ago.

Losing her job, it turns out, may have been Tan’s biggest lucky star. It wasn’t long until Tan had a book contract and was flying across the Atlantic, where she would restitch her family history by learning how to make her Auntie’s Khar Imm’s pineapple tarts, Auntie Khar Moi’s mooncakes, and her Auntie Alice’s Teochew braised duck, and along the way, set the stage for her own future. …

In both books, the theme is food and how it shapes us, comforts us and opens up our hearts. Tan, through discovering her own family history, uncovered parts of herself that she didn’t know existed. Ciezadlo, a Chicago-born freelance writer, goes to war and finds humanity all around her. Both are personal and culinary culture rides into another place and time — juicy, evocative and thoroughly entertaining and served up with a side of humor. That’s something especially welcome at 6:15 in the morning.

ArtsCriticATL.com, September 25, 2011 (back to top)

Book review: Cheryl Tan chases food memories and family in A Tiger in the Kitchen

By Parul Kapur Hinzen

Dark soy sauce, sour plums, ginger, bird’s-eye chilies. The memory of these biting, hot, piquant flavors of Singaporean cuisine ignite Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan’s longing for home as she chases stories in New York, a fashion reporter for The Wall Street Journal. But it’s a particularly mad desire to taste her grandmother’s buttery, jammy pineapple tarts again that drives her back 10,000 miles around the world.

Tan’s beloved pineapple tart, like Proust’s crumbs of tea-soaked madeleine, evokes a history and a family life that has all but disappeared for her. Her tart-making Tanglin Ah-Ma, we learn in “A Tiger in the Kitchen,” died years ago when Tan was eleven. In any case, the festive tarts were only made on Chinese New Year, one of the few times of year that Tan met her father’s family, from whom her parents were estranged.

“A Tiger in the Kitchen,” Tan’s engaging account of several cooking trips to Singapore, offers the domestic drama of a career woman struggling to make the dauntingly labor-intensive foods of her ancestors — rice dumplings steamed in an origami of bamboo leaves, a fish mousse that’s a two-day procedure. What makes the book poignant is that Tan gradually exposes the tears in the family’s fabric and her tentative attempts to mend broken relationships. She is tutored first in baking the tarts of her childhood by her kindly Auntie Khar Imm, who is well-versed in their production (stew 70 pineapples for 3,000 tarts). Then, like an anthropologist at the stove, armed with notebook and camera, she unearths a full repertoire of special dishes from both her father’s and mother’s sides of the family. Through this culinary apprenticeship, she warms our hearts a little as we watch her grow attached to family members she grew up almost not knowing at all.

“‘Why did I have to have a Tiger daughter?’” Tan recalls her mother complaining when she decided, at age eighteen, to leave Singapore for journalism studies in the United States. “If you were born in the olden days in China,” she’s told, “you would have been killed at birth!” With a streak of pride, Tan explains that girls born in the Year of the Tiger are feared as rebellious, aggressive, fierce. Emboldened by her zodiac reputation, and inspired by her father to aim high, the teenage Tan makes the Pulitzer Prize a career goal. Traditional women’s work like cooking and keeping house doesn’t register in her consciousness.

What a difference a couple of decades make. Tan marries a fellow journalist. She turns to baking in her Brooklyn kitchen as a way to relieve workaday stress. The blazing ambition of youth dims further after she loses her prestigious reporting job in the economic downturn. She arrives at that turning point so many of us do, as we outgrow youth, where the future is no longer the only compelling point in our lives. The past now surfaces — Tan is troubled by a gnawing appetite for the foods she was brought up with, especially the cookery of the ethnic Chinese Teochew people of her father’s side.

Gathering recipes from her aunties proves instructional in ways Tan, perpetually anxious about measurements and cooking times, doesn’t anticipate. The preparation of duck soup, with the bird’s beak and eyes intact, or the stuffing of mooncakes with lotus-seed paste, involves intimate hours in a relative’s kitchen, during which talk brings to light shame and pain suffered on both sides of her family, especially by her grandmothers. Her Tanglin Ah-Ma, the superb cook she barely knew, was neglected by a husband addicted to gambling and opium. Tan learns her mother’s mother fared no better, tossed aside by a bigamist husband who favored his first family. Both grandmothers, she discovers, had to compromise themselves by opening gambling parlors in their homes in order to feed their children.

There is also the central rift that defined Tan’s childhood, the estrangement of her family from her father’s people, begun, she hears, when her mother gravely disrespected her father’s parents. Tan wonders if this long-ago dispute fatally undermined her parents own marriage, because they are divorced after decades together in a culture where divorce is a matter of deep shame. She affectingly describes her embarrassment at meeting her father’s new bride for the first time, a provincial Chinese girl younger than she is, yet ends the anecdote with a wisecrack. In this story of family heartbreaks, Tan both glances at and quickly turns away from wounds with her buoyant prose. The journalist in her seems to shy away from emotion as though its unveiling is, somehow, unbecoming and unprofessional. As though she is most comfortable training her eye on the known world, avoiding the murky complexities of the inner self.

Earlier this month, after a reading at the Decatur Book Festival — I had the privilege of introducing her — Tan was guest of honor at an Asian journalists’ dinner at the Iberian Pig on Decatur Square. I was impressed at the wide array of tapas she sampled, an obviously energetic omnivore, a genuine foodie from that most food-obsessed of cities, Singapore, whose mélange of Malay, Chinese and Indian cuisines has given rise to a sumptuous culture of street food. In her book, Tan mentions tucking into oyster omelets and stir-fried radish cakes as soon as she lands on home ground at a hawker center near the airport. Back in New York, she describes her enthusiasm for the online foodie community and a particular Twitter challenge she takes up to bake her way through a famous bread maker’s bible, with all the picture-taking and blogging that attends such participation. Tan seems to joyously align her efforts to retrieve the old food traditions of her family with a vigorous endeavour at communal bread making through the innovations of online technology.

In “A Tiger in the Kitchen” she demonstrates that there is still hope for those who have strayed from tradition, which must be a good percentage of the human population in the twenty-first century. For if you have the heart and determination, Tan shows you can go home and learn to cook like a fiend, and maybe even, sometimes, like your grandmother.

Lonely Planet, December 14, 2011 (back to top)

Travel Literature Review: A Tiger in the Kitchen

A Tiger in the Kitchen by Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars

Reviewed by Jani Patokallio

A Tiger in the Kitchen is subtitled A Memoir of Food and Family, and fans of South-East Asian cooking will definitely want to get their hands on this book. The idea behind the book is simple: author Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan, American fashion journalist and amateur cook, heads back to her native Singapore to learn to make the all the classic Teochew dishes she’d eaten as a child. Her culinary misadventures and apprenticeships in the kitchen are told with wit and verve. The loving descriptions of food – the ‘intoxicating fog of turmeric and lemongrass seeping into the air’ from a freshly steamed batch of otah, steamed bak-zhang glutinous rice dumplings with pork filling ‘a shade of bittersweet chocolate’ or the ‘deliciously grassy and vanilla-like’ scent of pandan-skin mooncakes – get the salivary glands racing. A passing familiarity with Singaporean cuisine will increase the hunger pangs, although the book remains quite readable even if you can’t quite tell tau yew bak from bak chor mee. Best of all, the book includes ten detailed recipes, so you can even take a stab at making them yourself.

The family side of the memoir is a bit of a mixed bag. Tan’s claims of being a rebellious tiger are somewhat undercut by her childhood of posh private schools and social clubs, coupled with a mildly irritating habit of brand name-dropping (a shopping trip to Stella McCartney in Paris here, a dinner at Per Se there). For her supporting cast, the very first page of the book has a family tree boasting 35 people, each of whom has several nicknames and forms of address, and attempting to keep track of the various Gong-Gongs, kukus, Tanglin ah-mas and aunties soon becomes an exercise of Dostoyevskian proportions. Fortunately, you don’t really need to, as they are mostly only there to spice up the story with anecdotes and recipes and the lightweight plot is easy enough to follow.

All in all, a deep travelogue this is not, but if you’d like to vicariously eat your way through Singapore, take a peek inside a Nonya kitchen and have a nifty stack of recipes left over, add this book to your shopping cart.

The Charlotte Observer’s South Park magazine, July 8, 2011 (back to top)

Read It: A Tiger in the Kitchen

By Rachel Sutherland

When you think about it — or at least when I do — the tenets of fashion and cooking are strikingly similar.

Both require an understanding of basics, including proportion and technique and a willingness to experiment, to take chances. To excel at either, one must have confidence. Both are often informed by ones childhood or upbringing.

And while recipes or instructions are good, there’s often no exact right answer. You just know when it works.

So then it’s no surprise that I so thoroughly enjoyed A Tiger in the Kitchen: A Memoir of Food And Family, By Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan, a NY-based writer who has written about fashion (imagine that!) for InStyle, the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal.

Cheryl’s story connected with me on so many levels, and not just because she was the unofficial ringleader of the regional press corps at NY Fashion Week. When I was the Observer’s Style Editor covering fashion week for the first time, she welcomed me into the fray with open arms though we had never met.

The book resonates because I too, like many women I know, struggle with finding a seemingly impossible balance between tradition and modern feminist ideals inside the kitchen and in the workplace. And, of course, when you toss in a wicked love of designer goods (Cheryl was part of a pre-economic crash team of reporters covering luxury goods for the Wall Street Journal), you’ve got yourself a situation only the most home-y food can fix.

Though set against a backdrop of finding her Chinese-Singaporean roots through her family’s favorite dishes, Cheryl’s is a relatable story of life’s true priorities making themselves known when and how you least expect it. Say, when you’re learning how to make pineapple tarts and gambling rice with your aunties in Singapore or baking bread with your Twitter friends.

The chatty, sweet and funny tone of A Tiger in the Kitchen is only augmented by the 10 recipes for Singaporean dishes she so lovingly describes in the trade paperback. $14.99

BookReporter.com (back to top)

A TIGER IN THE KITCHEN: A Memoir of Food and Family

Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

Voice/Hyperion

Memoir

ISBN: 9781401341282

Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan was born in the year of the Tiger — not a particularly auspicious beginning for a baby girl in traditional Singapore. Tigers are passionate, determined and headstrong. Rather than following the traditional route and learning to cook as most girls do, Tan was all about education and ambition. Encouraged by her father, she followed her heart and chose a path that took her from the small island where she was born to the vast shores of America where she settled on the East Coast.

Years passed, and her desire for the addictive dishes of her homeland overwhelmed her. The images and memories of culinary delights, lovingly prepared by the sisters of her mother and father, such as Teochew Braised Duck, Popiah, Bak-Zhang, Pandan-Skin Mooncakes and Pineapple Tarts wafted across the miles and lured her back to the kitchens of her native land.

After a life-changing event, Tan found herself with time on her hands and so began the year-long commute from New York City to Singapore. As a tentative cook, the intricacies of Singaporean cooking seemed overwhelming at first. As the year passed, however, Tan found herself becoming increasingly comfortable preparing dishes that nourished her body and her soul. Armed with an ink pen and notebook, she recorded not only the steps to recreate the recipes she so strongly desired, but also many of the memories, stories and family history that accompanied her cooking lessons with the women she loved and admired. A TIGER IN THE KITCHEN was born.

Here, Tan shares with us the journey that reconnected her with her Singaporean roots in a new and different way than ever before. The love and acceptance she finds in these kitchens are a far cry from the competitive business world of New York City, and she blossoms and grows during her numerous trips back home. She also elaborates not only on her adventures in native cooking, but on her love of baking bread as well. Tales of successes and failures with bagels, light wheat bread, ciabatta and focaccia shed additional light on the development of Tan’s skills in the kitchen.

A TIGER IN THE KITCHEN is a mouth-watering true tale of one woman’s reconnection with her roots and the cuisine of her formative years. Weighed down with the stress of a career in one of the most competitive cities in the world, Tan embraces the unexpected 12-month sabbatical that takes her home again and allows her to view her family members and herself in a new light. While the book focuses on something humans have been doing since the beginning of their existence — gathering, preparing and eating food — Tan connects it to our hearts, emotions and general well-being in a special way. As you read it, you’ll find yourself considering the food of your younger days, no matter what your heritage, and remembering with love those who prepared it for you.

— Reviewed by Amie Taylor

Serious Eats, April 24, 2011 (back to top)

Serious Reads: A Tiger in the Kitchen, by Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

By Leah Douglas

For many cooks, receiving recipes and culinary knowledge from past generations is crucial to their personal development. Some are lucky enough to have their family’s recipe book ingrained at a young age; others strike out on their own without their mother’s lasagna or chicken soup recipe. Journalist Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan spent much of her young adulthood not knowing how to cook. The story of how she embraced her Singaporean heritage and traveled to her home country in search of her delicious memories is detailed in A Tiger in the Kitchen: A Memoir of Food and Family.

a35565

After nearly two decades of living independently in the U.S., Tan realized that she had never really learned how to cook. Sure, she could whip up pasta or an occasional cake, but the spicy, hearty, delicious dishes of her Singaporean youth were fading from memory. Something of a rebellious child, she had chosen to study hard and play with her friends rather than learn how to prepare a home. As she came to realize that her kitchen disasters were more a chronic condition than a 24-hour bug, she decided it was time to take action.

Tan led a whirlwind lifestyle as a fashion columnist, traveling all over the world and spending long days researching, writing, and snagging interviews with elusive designers. The stress caused her hair to fall out and her patience was wearing thin—and then, she lost her job. While certainly thrown for a loop, Tan didn’t despair. She seized the opportunity to dedicate a year to traveling to Singapore, reuniting with her family, and learning how to cook from her aunties and grandmothers.

Initially, she was not well-received. Not only had she left Singapore for the United States and lost touch with her roots, but she also returned home without a child for her aunties to coddle. She struggled with unpracticed Mandarin and even rustier Teochew, hoping that her voyage would yield the culinary insights she was seeking. Slowly, the aunties began welcoming her into their kitchens, revealing the secrets to fresh summer rolls, salted vegetable and duck soup, mooncakes, and her grandmother’s famous pineapple tarts.

Tan tried desperately to scribble measurements in her notebook, but was consistently chided for her efforts. She was told to “agak, agak!”, or “guess, guess!”, adjusting ingredients to taste rather than according to a recipe. Tan was at first terrified, but soon became more confident in her ability to prepare these dishes on her own. Her culminating project was a Chinese New Year dinner prepared for her whole Singaporean family. She slaved over the traditional items, which were approved by her aunties with groans of delight.

Many of us wish to return to our culinary roots, to rediscover the recipes and tastes of prior generations. Tan flew halfway around the world, leaving her husband for weeks at a time, to glean as much knowledge as she could from her aging relatives. Her book concludes with just a few choice recipes, including the delectable pineapple tarts. She provides wonderful description of the Singaporean kitchens, ingredients, and chatter amongst the strong-willed women of her family. Her passion and appetite left me craving nothing more—except perhaps some great homemade mooncakes.

Brooklyn Bugle Book Club, September 9, 2011

(back to top)

A Tiger in the Kitchen by Brooklyn Heights Resident Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

by Alexandra Bowie

According to birth order theorists, oldest children tend to be cautious; their younger siblings are the creative risk-takers in the family (surround that statement with a lot of caveats, of course). There are some exceptions, one of them being the oldest daughters of two-daughter families. Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan, the author of the engrossing memoir “The Tiger in the Kitchen” is one of this special group.

Tan grew up in Singapore, a descendant of emigrant Chinese. She worked hard at school, consciously avoiding learning domestic skills as she studied. She went to the US for college and didn’t look back for 15 years. After graduation, Tan forged a career as a reporter, first at the Baltimore Sun, later at the Wall Street Journal, covering fashion and the related business. She married an American, and settled in Brooklyn. But at some point she realized she was missing something – the food. A couple of years ago a lay-off gave her an opportunity, and Tan took it: over the course of a year she made several long visits to her family in Singapore and, eventually, to the village her great-grandfather had left behind in China.

Tan spent most of her visits with her divorced mother and extended family on both her father’s and mother’s sides, learning her culture through its cooking. Tan describes one signal clash of cultures that was evident immediately: the only plausible explanation she could give her Singapore relatives for her extended visits away from her husband was that she was learning to cook so she could make him “good Singaporean dinners.” Tan brought the same skills she needed as a reporter to her cooking quest, and immediately found another place her several cultures refused to mesh in the approach to details. Having trained herself to be a successful free-lancer, Tan was interested in the minutiae: when? How much? Could her aunties and granny let her measure an ingredient before they added it to a pot? They laughed at her, saying “Agak-agak,” which Tan translates as “just guess.” As Tan let go of her need to know the details, she slowly learned to cook.

More important, as she ably demonstrates, over the course of the year Tan grew up. Tan writes her own brand of UK-inflected American English, and speaks her mind. She describes her mistakes, including a delightful story about second-guessing her forgetful grandmother. The comparison of the final products proved, that, contrary to Tan’s assumption, her granny had not omitted some important instructions. Tan also describes her cooking failures, most memorably a ciabatta that filled her apartment with smoke. Tan is braver than I am: she describes serving many of what she considers failures to her friends and family. As Tan learns through the course of the year, it’s not always a choice between career and cooking. Some lucky people combine them, as Tan now has – in addition to the book, her blog is a great source of recipes and food information. Her lengthy visits home taught her something fundamental. Over the course of that year, she more than came to terms with herself; in the words of one of her relatives, she learned to cook with her heart.

Tasting Table, September 1, 2011 (back to top)

Reading List

A Tiger in the Kitchen ($15) We’re all for time-consuming culinary projects and will happily forfeit a weekend to cook the perfect cassoulet or practice baking bread. But Cheryl Lu-Tien Tan took dedication one step further when she traveled back and forth from her home in New York to Singapore for a year in order to learn her family’s cuisine. The contrasting narratives of her life as a fashion journalist and her foray into the unpredictable and instinctual styles of cooking in Singapore (not to mention the hunger-inducing descriptions of the dishes she tackled) kept us sated through the final page.

Hyphen Magazine, June 15, 2011 (back to top)

Review of A Tiger in the Kitchen: A Memoir of Food and Family

By Eric Zhang

When I was younger, my mother used to make a very simple dish when she was too tired to cook: stir-fried tomatoes with eggs, sometimes served with thick, starchy noodles, sometimes with plain white rice. Even though it was a quick and easy dish, to me it was a delicacy. Mildly acidic, just a little bit sweet, with a hearty amount of scrambled eggs, it exemplified comfort food at my Chinese American dinner table. It was more than just a meal: it was the warmth of home.

In A Tiger in the Kitchen: A Memoir of Food and Family, Singaporean expat Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan similarly uses food as a vehicle to navigate the often complicated relationships that Asian Americans and Asian immigrants often form with regard to broader ideas of family and home. Despite her complete lack of knowledge of the kitchen, Tan sets out on a mission to master the beloved Singaporean dishes of her late paternal grandmother, who was nicknamed “Tanglin Ah-Ma” after the Singapore neighborhood she lived in. Along the way, Tan unravels her family’s forgotten histories and the complexities of her own identity.

As the firstborn child, Tan was raised to strive for opportunities outside the domestic confines traditionally expected of women. Placing her education and, later, her career at the top of her priorities, Tan never considered learning to cook to be an important responsibility. Nor was it a major concern for her family: “Mum and her two sisters were a rambunctious lot for whom learning skills that would make them more marriageable (like cooking) was low on the list of priorities. […] Their independent streaks would eventually land them successful husbands who could afford maids to do the bulk of the cooking.”

When unexpected events in Tan’s life — the loss of her job, her father’s minor stroke — led her to reconsider the significance of home and family, she reached out to her aunties Khar Imm, Leng Eng, Khar Moi, and Alice, her maternal Ah-Ma, and a bevy of other friends and relatives in a quest to dominate the stovetop. Her journey takes her from her tiny New York kitchen to Singapore, her childhood home, through Shantou, China, the land of her ancestors, and even to a pit stop in Hawaii, the home of her Korean mother-in-law.

The heart of the story lies in Singapore. In the context of Tan’s quest to explore food and the domesticity of the kitchen, the city itself and its colonial history add a complex layer to the idea of ethnic identity. For example, Tan’s sprinkling of Mandarin, Hokkien, Teochew, and Malay words and phrases throughout the narrative suggests a mixing of diverse communities and adds a certain cultural tension. “My inability to speak any Teochew, the Chinese dialect that [Tanglin Ah-Ma] spoke, meant we mostly sat around with me feeling her eyes scan over me, inspecting this alien, Westernized granddaughter she had somehow ended up with,” Tan recalls.

The recipes, too, examine the idea of cultural heritage in a nation whose history is marked by immigration and colonialism. With influences from various Chinese traditions, native Malay ingredients, and even Indian imports, Singaporean cuisine is a unique mixture both familiar and exotic to me, as an ethnic Chinese. My mouth watered at the bak-zhang Tan learns to make as I was reminded of the zongzi I too grew up eating. I tried to imagine what Ah-Ma’s kaya must taste like (which proved difficult as I am completely unfamiliar with the flavor of pandan leaves, an apparently essential Singaporean ingredient).

Tan’s New York apartment plays an important background role in the narrative as well. Punctuating her forays into Singaporean cooking, Tan concurrently takes on a bread baking challenge in the States, allowing her to indulge in cinnamon rolls and homemade bagels. The dichotomy between carefully measured baking and the agak-agak (a Malay term meaning to guess) philosophy of her aunties plays out spectacularly in a failed attempt at makingciabatta that nearly burns her kitchen down. “I’d been instructed by my Singaporean aunties to live by agak-agak and have faith in my own eyeballing. But baking was a completely different thing.” Though she initially considers the two to be diametrically opposed, she later learns that Singaporean agak-agak and Western precision are, in fact, complementary skills.

Tan’s prose is conversational and frank, adding explanation when necessary to translate foreign words and concepts. Often self-deprecatory, Tan communicates her own frustrations with her inability to cook with a personable sense of humor. Her vividly sensory descriptions of the smells of the kitchen also manage to induce sudden salivation and hunger pangs without dipping into heavy-handed metaphor.

When I moved out from home to go to college, I constantly attempted to recreate my mother’s tomatoes and egg, to the extent that it’s even become infamous among my non-Chinese friends. No matter how many variations I tried, I never got it quite right, even after researching recipes online and asking my mother herself for her technique. Like Tan’s aunties and their agak-agak, my mother is not always helpful when trying to explain how to cook. “Put a little bit of this, a little bit of that.” Though I used to be frustrated with the guesswork involved in trying to decipher her recipes, I understand now that it doesn’t matter if I don’t get it perfect. “I realized that the point hadn’t truly ever been the food,” Tan concludes, and I agree.